10 May Matisse, the Fauvist and the Spider

Author : By Romain Méfret.

Everything has been said about Henri Matisse. His work, which remains unclassifiable, has been dismembered, dissected and stored quietly in airtight compartments. Everything has been said … Everything and its opposite. Because it’s not easy to label a giant. Sixty years after his death, the work of an artist who kept his distance from classical representation as well as abstraction, remains an enigma and continues to mesmerize.

Nothing predestined young Henri, born in 1869 to a small bourgeois family in northern France, to become the great Matisse. His childhood spent in Bohain-en-Vermandois, on the banks of the Somme, was devoid of storm and stress. Too young to remember anything about the war of 1870 which forced his parents, who were grain merchants, to leave Cateau-Cambrésis for the Province of Saint-Quentin, he grew up in the emerging Third Republic in the whirlwind of the end of the nineteenth century, with a backdrop of industrial, cultural and social revolutions. But the tune of history barely reached his ears and he seemed to have no inclination to go in this direction. He quickly joined a law office as a clerk and was the pride of his parents. But fate is facetious and plants mocking seeds in unexpected places. An acute attack of appendicitis suddenly kept him away from his desk. Leon Bouvier, the brother of his friend and neighbor Leon Vassaux, showed him his first attempts at painting which piqued his curiosity. His mother, an amateur painter herself, quickly understood that her convalescent son had contracted a disease from which he would never recover. That is when she offered him a box of paints. His quiet life as a lawyer had just toppled forever. He tried working at the dusty offices of the lawyer Derieux, but the virus had its way with him. In 1890, he stopped practicing law completely. In 1891, he moved to Paris where he attended the prestigious École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts. Matisse was being born.

The impossibility of reality

While at the Beaux-Arts, he met Georges Rouault and Albert Marquet, and attended the classes of Gustave Moreau, one of the few professors at the time who opened the minds of his students to all artistic movements. “He was a cultivated man, who encouraged his students to consider all forms of painting, while the other professors had a single period or style in mind – that of contemporary academic painting – that is to say their own, the residue of all conventions,” said the young apprentice of his teacher. Alongside his studies, Matisse made his artistic debut as a copyist at the Louvre. His success was dazzling and embarrassing: he was being recognized for barely painting – all he was doing was copying! The foundations of his art began to take shape: it was clear to him that reality and art were hopelessly irreconcilable. And so he left the shores of classical representation to embark on a journey towards unexplored territories.

Painting paintings

In 1897, he exhibited his first works at the Salon des Cent and at the Société nationale des beaux-arts, as associate member, and then met John Peter Russell who introduced him to Rodin and Pissarro. The new world of Impressionism came rushing in at him. Influences multiplied, his brushwork was refining itself, but was not yet completely free. Cézanne was present in his early works, such as Pink Wall, which he painted in 1900 during a stay in Corsica. But something important was happening during those years. While staying in London, he fell under the spell of J.M.W. Turner’s work. Suddenly, light was at the center of Matisse’s concerns. Upon his return, he worked at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, under the direction of the great Antoine Bourdelle, sculptor and graphic artist of genius, who was the mentor of many of the greatest artists of the twentieth century from Matisse to Richier, including Giacometti. But it was thanks to the savvy and talented Eugène Carrière that he made his most crucial encounters: Jean Puy, André Derain and especially Maurice de Vlaminck.

The Tiger Brigades

Matisse’s art experienced its first revolution. And revolutions always take place amid sound and fury. In 1905 at the Salon d’Automne, he exhibited alongside Marquet, Vlaminck, Derain and Kees van Dongen. The event caused an instant scandal. Viewers of the time were not ready for such a brutal break. His flat bright colors were like stabs in the belly of classical representation. The stunning simplicity of his brushstrokes raised quite a stir. The critic Louis Vauxcelles was right: this Salon d’Automne was a real “cage of wild beasts”, « fauves » to use the French word. The expression took hold; the rebels adopted it immediately. Fauvism had just pulled off its first feat – its first coup d’état.

Observers at the time did not recognize what was at stake: the emancipation of painting and especially the revenge of color over drawing, sensuality over spirituality.

Cézanne led the charge, the Impressionists cleared the ground, and the “Fauves” bulldozed the remains.

From scandal to reverence

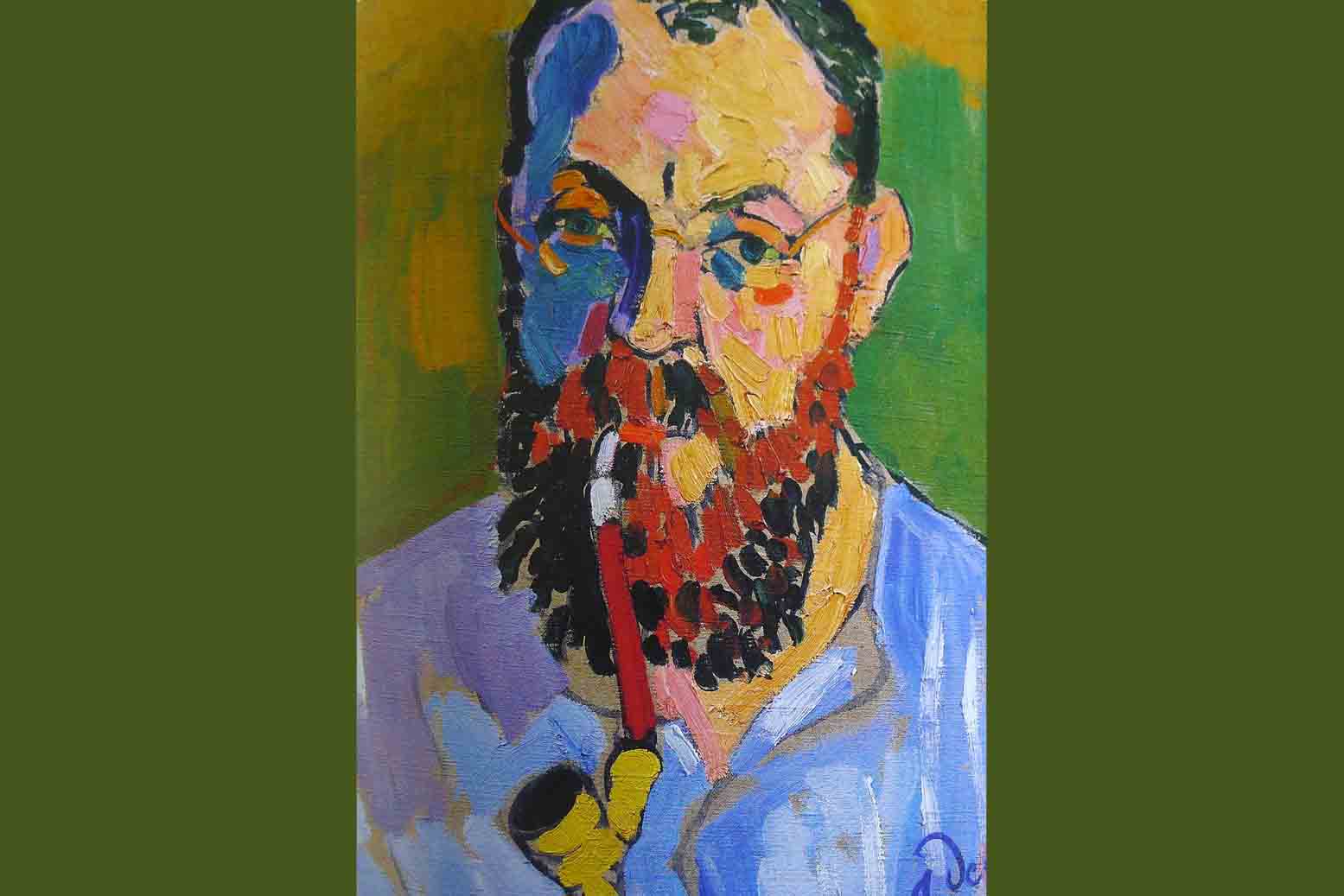

The evolution between The Pink Wall (1897), Luxury, Calm and Pleasure (1904) – very impressionistic, Woman with a Hat (1905) – still classical, and The Joy of Life (1905), View of Collioure (1906) or Portrait of Madame Matisse was staggering and amazed everyone. The French greeted it with venom. But the art world was already toppling. Other strongholds grasped the scope of Matisse’s avant-garde work. In 1908, his works were exhibited in Moscow, Berlin, Munich and London. In 1913, they were exhibited alongside paintings by Duchamp and Picabia at the Armory Show in New York, a real laboratory of modernity. In France, people were happy “to see among the admirers of Matisse only Russians, Poles and Americans.” It was not until 1925 that the painter was finally recognized as a prophet in his own land.

The Côte d’Azur as adopted land

Like Gauguin, with whom there is an obvious connection, Matisse traveled extensively. But no place inspired him like the Côte d’Azur. He returned the favour by leaving his indelible mark on it. Forced by the ravages of the First World War to leave Collioure where he had settled in 1905, he settled permanently in the south of France, in Nice, in 1916. “When I realized that every morning I would see that light again, I couldn’t believe how lucky I was,” he enthused. He never strayed far away from this land “where light plays a leading role and color comes second… Above all, we must feel it, have it inside…” Matisse created his greatest works there, perfecting his art, relentlessly exploring through both painting and sculpture the relationship between drawing and color, line and object, substance and form. One of his greatest artworks is located in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, where he moved in 1943 to get away from Nice, which was threatened by bombing. There he agreed to decorate, almost predictably, the Rosary Chapel out of friendship for one of his models the Dominican nun Sister Jacques-Marie. At first, he simply thought he would redraw the stained glass windows, but he ended up tackling the entire place. “This work required four years of hard work that took all of my time, and it is the result of my entire working life,” Matisse wrote to Father Couturier, at the inauguration of the chapel in June 1951. Three years later, at the height of his fame, he died and was buried in the cemetery of Nice at Cimiez, his adopted homeland.

Between two shores

Meanwhile, Matisse had created some of the most important artworks of the twentieth century. In addition to his countless paintings, we must not forget, among other things, his monumental series The Dance, created for the collector Albert Barnes, his cut-out gouache series Jazz, his book illustrations (The Flowers of Evil, Ulysses…), his Nudes and sets for the Song of the Nightingale commissioned by Stravinsky and Diaghilev and those of the Red and Black for the Ballets Russes of Monaco. Though his prodigious work has without a doubt left a permanent mark in art history, inspiring tremendous geniuses (Pollock, Rothko, Newman, Moll, Purrmann …) and though the “fauvists” revolutionized their time and turned painting values upside down, Matisse’s work cannot be considered ideological, as was so often the case during the turbulent twentieth century. His childhood and past as an unimportant provincial clerk, his life as a loving husband and his attitude of peaceful artist (far from the cliché of the tormented genius) speak to this. “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity, serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, that would be for every mental worker, for the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue,” he wrote in 1908. Above all, Matisse was a hard worker, capable of reproducing hundreds of times a single sketch before painting a simple apple.

Thus, the child of color had a huge influence on the abstract and conceptual art movements that engulfed the twentieth century, but he always kept his distance from those lands. The great destroyer of classical representation never severed the connection that figurative art, like a spider’s thread, provided him with what is real. French Door at Collioure (1914), the most abstract of his paintings, remains solidly on that side of the world. Matisse stands proudly between the classical point of view – “one eye on the canvas, half an eye on the pallet and ten on the model” – and Kandinsky’s celebration of abstraction – “ten glances on the canvas, one on the pallet, half of one on nature”. It is precisely this attitude that characterizes the uniqueness and strength of his work. A radical he was not; a visionary, most certainly. In any case, eternally modern. “I know that only later will people realize how what I do is in line with the future.”

Caption:

French door at Collioure: created in 1914, French door at Collioure is the most abstract work of Matisse, who never reached the shores of abstraction.

The Sorrows of the King: Shortly before his death, Matisse painted a last self-portrait, The Sorrows of the King, a perfect representation of the position of the artist, between classical representation and abstraction.

Blue Nude: Matisse’s obsession will have been to cut to the quick the relationship between line and color. In Blue Nude color serves as both substance and form.

Portrait of Madame Matisse: Still influenced by classical portrayals, Portrait of Madame Matisse marks a major turning point in the artist’s work. Fauvism is being born.

Saint-Paul-de-Vence: Matisse hosted Gide, Rouveyre, Picasso, and Aragon in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. Out of friendship for a Dominican nun, he decorated the chapel of the Rosary, an artwork that will become the painter’s masterpiece, his spiritual testament.